Aww, aren’t you adorable, chillin’ and scrollin’ and surfin’ the webs. Did you realize that in only one precious second, you can morph into a monstrous maniac, evolving into a full-on Rambo, raining real damage and even making the news? Once our rage circuit is actively engaged, we can’t control it, as much as we’d like to think “I got this.” It has nothing to do with insanity or mental instability. The countless stories of seemingly “normal” people who suddenly lose their shit are consistently proving that there are pathways in the brain — yes, your brain! — that can result in violent, ugly, aggressive outbursts, for better or for worse. You’ve been warned: don’t make us angry. You don’t want to make us angry.

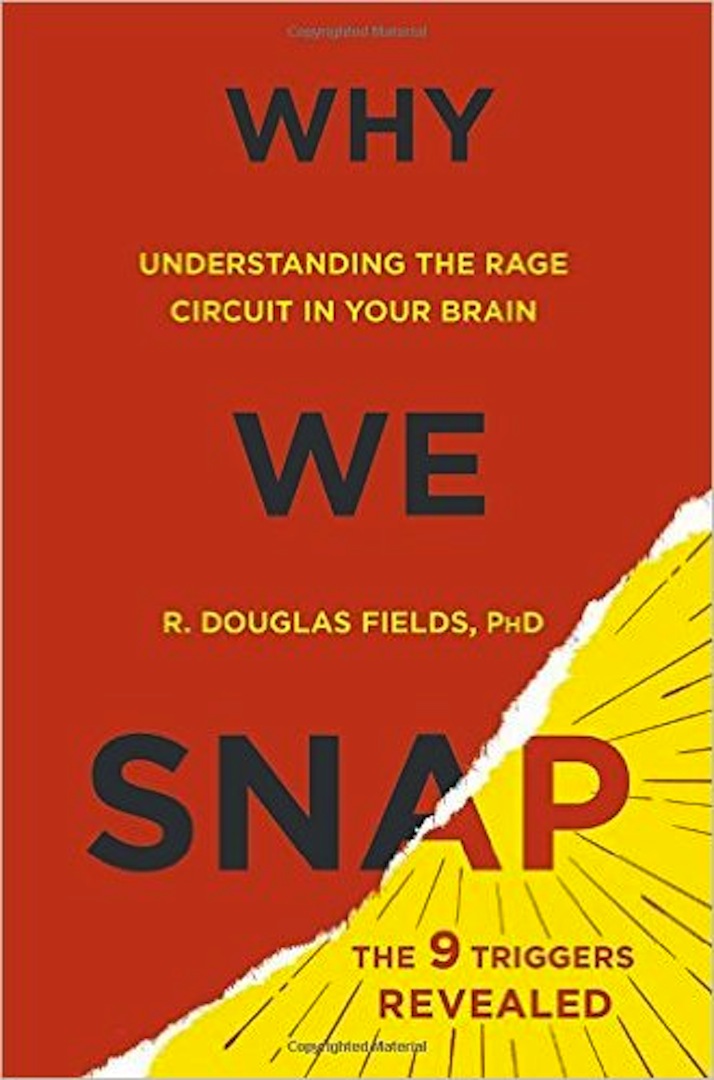

R. Douglas Fields is a senior investigator at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, and is a prominent writer in the field of neuroscience. His new book, Why We Snap: Understanding The Rage Circuit In Your Brain, details his research regarding suddenly violent behavior and the extraordinary strength, influence and relevance of our evolutionary hardwiring. Doug says there are nine precise triggers that can make anyone snap like a twig — even li’l ol’ you.

Here, we respectfully ask Doug about some of the darkest and scariest mysteries of human behavior. Dig:

What a subject! How did the idea of “rage triggers” occur to you?

I was traveling to Barcelona to give a lecture on my neuroscience research. Normally, I travel alone, but I was with my 18-year-old daughter. We had a little bit of time before the lecture, so I thought we would go [sightseeing]. At the Metro station, I felt a tap on the pocket on my knees — I was wearing cargo pants. I felt that my wallet was gone. I reached back, grabbed the robber by the neck and threw him to the ground, and proceeded to get into a struggle to get my wallet back. I’m rolling on the ground with the robber. At this point, a thought bubbles up to my consciousness: what the heck are you doing? I realized that I had just risked my life and limb in an instant, by something in my environment. It involved no conscious thought at all. So the idea that we are not in control in these types of situations led me to wonder: what is the neurocircuitry in this?

Would you consider yourself a lover or a fighter?

I need to clarify: this is really out of character for me. I have graying hair, and I am about 130 pounds. I don’t have any military experience or any martial arts experience. What that taught me is that we are all wired for violence. We have the behavior for violence. It is wired into our brain. We have it because we need it, as a species, to protect ourselves and to protect our young, to get food.

So let’s get physical. Give us the lowdown and let’s zero in.

The circuitry for violence is in a part of the brain that is unconscious, in what is called the hypothalamus. It’s a part of the brain that controls other powerful urges unconsciously, like feeding and sex and thirst. If you stick an electrode in this part of the brain — the hypothalamic attack region — and you stimulate it — an animal will launch into a vicious attack and kill another animal. That raises the question: what feeds into this circuitry? What causes this response? Because that’s clearly what happened to me [in Barcelona]. New methods and insights in neuroscience are revealing that circuitry.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but common wisdom states that you should never get into a scuffle with a robber in the Metro station.

This is what disturbed me so much. You don’t want to get into a fight with a robber. It’s dumb. But I didn’t think. Then I realized that the reason that this circuitry is in our hypothalamus — in the unconscious brain — what we are really talking about — is part of the brain’s threat detection mechanism. So the approach to this book is not psychology; it takes a neuroscience approach, understanding that all behaviors are controlled by the brain. What are the circuits that control these specific behaviors? This is part of the brain’s threat detection mechanism. A huge part of our brain — and the brain in most animals — is dedicated to threat detection. We’re constantly taking in information about our external and internal environments, and this is all unconscious.

Why unconscious and not conscious?

There are two reasons. First of all, circuitry for consciousness is in the cerebral cortex, and that’s way too slow. Two: the amount of information that your unconscious brain is taking in vastly overwhelms the capability of the conscious mind to comprehend it and hold it. So it’s not only why I snapped when that burglar grabbed my wallet — how did I know he was there? I didn’t even see him [at first]. That’s all part of the circuitry.

This unconscious deal is not always a bad thing, right?

We have these circuits because we need them. But they occasionally misfire. When they operate normally, as they do most of the time, we call it “quick thinking” or “heroism.” A hero will act aggressively to come to the aid of someone else. Afterwards, people will ask him why he did that, and he’ll say, “I don’t know. I didn’t even think. I just did it.” So this book is not just about negative violence; it’s also about the circuitry when it works right.

I interviewed a lot of people who depend on this circuitry: extreme athletes, drivers of a Formula One race car — they can’t actually control that consciously. They are relying — in emergency situations — on these rapid response circuits.

We tend to equate violence — and violent outbursts — with instability and even insanity. Should we?

We tend to view violence as pathology. The fact is, most of the violence that goes on every day is not caused by abnormal mental illness. It’s caused by this circuitry. It’s aggression that we all have, getting tripped inappropriately. Everyday domestic violence, barroom brawls, this is the kind of violence that fills every day. This impulsive violent response is not due to mental illness. Yes, there is evil, and deliberate brutality and crime. But, by and large, it’s this misfiring that we all have in our brain that gets unleashed and causes the violence that we’re dealing with. And if we can understand it at a neurocircuit level, then we can begin to control it.

How did you come upon the nine triggers that make us snap?

There are nine triggers, but that’s too many to remember. Neuroscience has shown that you can only remember seven items in a string, like a phone number. I gave them new names — not scientific names — I used F for family instead of “maternal aggression,” which is what scientists use. I used L for “life or limb,” instead of “defense aggression.” Using a mnemonic , you can quickly identify when you feel a sudden rise in anger, say on the road. You can identify which of these triggers has been tripped.

Fear plays a large part in this too, correct?

Fighting, violence, aggression — that’s very dangerous behavior. You’re risking your life or limb to engage in this. No animal will engage in violence except for very specific reasons. That’s why you feel fear after you’ve done it. You can freeze in fear, or you can fight or you can flee. It’s all part of the mechanism of the brain’s threat detection.

Is there a gender difference in rage?

One thing that I really was struck with: the male/female differences. 90% of all the people in jail for violent crime are men. But 90% of all the people given an award for heroism by the Carnegie Foundation are men. A quarter of those men gave their lives. I don’t think we’re grappling with this subject honestly at a national level. Statistics say that 20% of all women have been sexually assaulted. It really opens your mind to the need to understand the biological basis of rage. We’re talking about biology here. All cultures are violent to women, and that is biology.

What struck you the most about researching rage?

I met so many fascinating people — from the Seal Team Six to elite athletes to the relatives of the Boston bombers. When I spoke to all of these people, I was struck by how interested and free they were with their stories, because all of them wanted to understand this. It seems like we are all trying to understand this.