How we sold our soul to the company store.

On The Flintstones, Wilma and Betty would start their engines for a shopping spree by chanting, “CHARGE IT!”

Very funny, until it wasn’t. Millions of years after the Flintstones fossilized, America is mired in debt, particularly credit card debt, with no payoff amount in sight. We’ve been collectively making minimum payments, compounded by insane interest, since the Stone Age.

Louis Hyman, an assistant professor in the Labor Relations, Law and History department at the ILR School of Cornell University, wrote a damn good book on the history of our credit/debt obsession/tragedy, called Debtor Nation.

He relates how debt was once considered — get this — shameful! And that banks, retail outlets and credit managers were actually reluctant to make with the honey, especially to ignorant slobs like us. That sure as hell changed, once the fat cats figured out how to make a buck from it. The curse then extended to all of us throughout these our United States, which includes a one-way ticket up Shit’s Creek, paddle not included.

If you owe on credit cards, or especially if you are young and being tempted by Satan at every turn, you owe it to yourself to devour and internalize this cautionary tale.

Here, Louis gives us a generous credit line:

The long history of credit and debt goes from the darkness to the light, but still remains a curse.

The overall question in the book is “how does personal debt move from the margins of American capitalism to the center?”

If you look at personal debt in the 19th century, people are borrowing, but they are borrowing at a local, small-scale level: from bartenders, from their brother, from the corner store.

By the end of the 20th century, [debt is created] through a succession of intermediaries, from global capital markets. You find that the largest institutions and the most powerful corporations are all centered on lending to consumers.

This was not the case in the 19th century. [The powerful people of the 19th century] were concerned only with building industry. This is a tremendous shift in American capitalism. So the question I wanted to answer is “how did that happen?”

At this point, regular people were not going to banks; they were going to loan sharks.

They had no alternative. In the face of usury laws, very wealthy people could borrow some personal money at a bank. For most average folks, that just wasn’t possible, so they either had to rely on their own personal networks or they had to rely on loan sharks, which, as you can imagine, charged clearly an arm and a leg. They charged hundreds of percent of interest a year. They had gangster-like ways to enforce the debt.

Reformers in the teens and into the ’20s tried to legalize small loan lending, what we would call “payday loans” today.

Back then, borrowing money was not the part of life that it is today. Then, it was a shameful secret that indicated weakness.

That’s right; any kind of borrowing, whether it’s for a mortgage, or for student debt, things that today would be a sign of respectability. No one is ashamed that they have a mortgage. They may complain about it, but no one is ashamed of it.

Part of it is someone else who would put you in their power. There was a social character to it, and that somehow you were being irresponsible for your investments, that you really didn’t own your farm if you had a mortgage on it. That begins to change in the 1930s.

In the 1920s, there was an expansion of loans through intermediaries, called finance companies. In the 1930s, there is a legitimization of mortgage borrowing through the Federal Housing Administration. Through this process, there begins to be a divergence in morality in some kinds of debt being good and other kinds of debt being bad.

More and more people have access through these new kinds of institutions. Finance companies and mortgage companies provide links to larger sets of capital. You start to see enormous amounts of money lent to middle-class and working-class people.

Automobile financing played an early role in credit lending for the middle-class.

Henry Ford was not a big fan of financing and [because he didn’t believe in financing], it almost brought down the Ford company. He was very hostile to finance, because it doesn’t make anything.

His anti-Semitism, I think, is rooted in his anti-finance stance, rather than the other way around. Ford doesn’t embrace lending to consumers at all, but General Motors did. GM founded The General Motors Acceptance Corporation [GMAC]. This is one of many initiatives to provide lending to consumers at first, and then there are copycats for all kinds of things. You could borrow not just for cars, but for vacuum cleaners, refrigerators, and other electrical conveniences. This new era of electrical products is made possible through this consumer credit.

Financing also led to the power of credit managers and department stores.

It’s sort of surprising that credit managers could be interesting. You wouldn’t think of them as sources of power.

The real question is “what is the role of credit in the retail firm?” Should it be something they do as a loss leader, or should it be something that actually provides profit to the company? Today we think of lending money to consumers as incredibly profitable, but in the early 20th century, small loans were incredibly expensive to process.

The department store begins to offer credit alongside other services, like giftwrap. They actually don’t make money on it until the late 1950s. When they figure out how to make money on lending to consumers [revolving credit accounts], they find that they are able to assume a new kind of power. This has all kinds of ramifications, not just for where profits are coming from, but also for gender and class relationships.

They’re caught in a financial catch 22. For department stores to compete with other stores, they have to keep lending money to their customers. By doing so, they start to put enormous amounts of capital into their credit offerings. They are unable to borrow from banks to cover these loans.

By the early 1960s, they have more money invested in consumer credit than they have in merchandise in the store. They have more money invested in the stuff they already sold than what they could sell to their current customers. The department stores begin to realize that something has gone horribly wrong. They are no longer in the merchandising business; they are in the credit business. They begin to find ways to sell off their consumer credit to third parties.

That’s where General Electric and GE Capital comes to the “rescue.”

In the 1960s, General Electric begins to take up the slack by offering to run the credit operations of retailers. This is how the American economy starts to change over from manufacturing to finance. By the 1990s, General Electric, a company we think of as a manufacturer, is now predominantly a finance company. This is a dramatic transformation, not just in retail, but in American industry.

This was a time when many people were denied credit just by their appearance, skin color or gender.

One of the things we take for granted today is that we always have credit scores, like The Fair Issac Company [now called FICO]. Back then, that was absolutely not the case. You would walk into a credit manager’s office, and they would evaluate you on all kinds of things: your clothes, your accent, where you work, your race, your gender.

This would not only not be legal today but it would make no business sense today. This kind of social relationship led to all kinds of curious contradictions. When married, middle-class women began to have really good jobs in the late ’60s and ’70s, they would find that they were unable to get credit, because the assumption was that only the husband would have a job and that the woman would just get pregnant and not be able to find work.

If you were a beautiful woman, it was hard for you to get credit because the assumption was that you would get knocked up. So the National Organization for Women would organize credit-consciousness-raising groups to thwart these kinds of issues. It was a big deal. By the ’70s, You needed to have credit to be part of the American consumer life.

There was a shift to this computerized FICO score, which gets rid of some of that discrimination. They would find other ways to discriminate. But that had other unexpected effects. Now people could be exactly pinpointed for what kind of interest rates to be given.

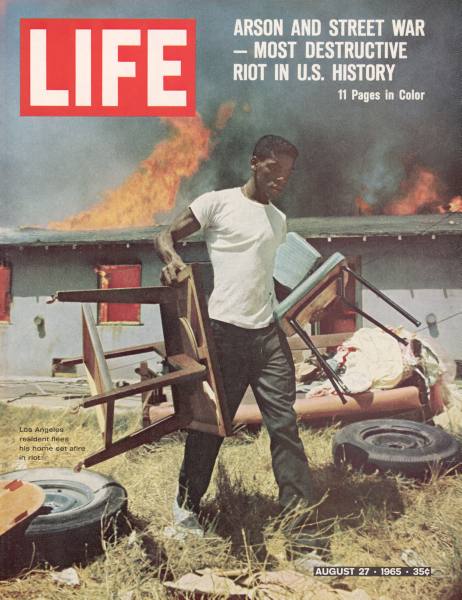

African-Americans faced intense discrimination when it came credit in the postwar years.

It’s a stunning difference. It’s not that a new credit system is created for African Americans, but that a new credit system is created for white people.

By the 1960s, the credit relationships are really only for white people. It’s an important part of understanding the urban riots of the 1960s. It’s not that black people were excluded from credit. Nearly everyone in the ghetto had a television set. It’s just that it would cost two-and-a-half times as much.

They were very angry about paying more for less and for being part of an older, more pernicious kind of lending system. During the urban riots [of the 1960s], people were burning the debt records, so that all these exploitative credit relationships were destroyed without a trace.

During the riots, it’s not: “we never had a television set, so we’re taking one.” It’s just that that exact same television set had been repossessed the previous week. They’re taking back what is already theirs in their mind.

I tried to put gender and race relationships at the center of understanding American capitalism. I think often that the stories we tell exclude those categories, but by doing so, that doesn’t make any sense, because those are the categories through which we live our lives.

This leads to the rise of VISA and MasterCard in the 1970s and 1980s, where the only color that matters is green.

In the 1950s, the big banks began to notice that people really like revolving credit at department stores, and they try to issue their own versions of it. It fails utterly. It’s very hard at first to convince stores to allow these cards to be used.

This changes around 1960, as Bank Americard begins to be issued by Bank of America in California. Bank of America had a wildly disproportionate share of the bank market in California. Because of that, they had access to large numbers of merchants and consumers. They were able to issue cards to customers and services to stores. They solved the chicken-and-egg problem. So Bank of America becomes a leader in issuing credit cards.

Throughout the 1960s, it spreads across the country and becomes the first national infrastructure. In response to this, all the other banks in California band together to form MasterCharge, which became MasterCard.

You can think of them as railroad networks, networks that are moving money around from customers to banks to stores. This allows for a wild new expansion of a common standard for credit to work at a national scale.

Which leads to securitization, when all the big boys want a slice of the pie.

By the 1980s, this has only penetrated to the top 20% of American households. But then you have something called securitization in 1986, which allows credit card debts to be resold onto capital markets, like the bond market. This allows securitization of American credit card debt for the first time. It allows enormous amounts of money to be lent to consumers.

You can see this emerge very rapidly in the late 1980s and early ’90s, when almost all of the debt issued comes from this securitization.

In the process, debt extends all the way down the socioeconomic hierarchy, so that people who can least afford to be in debt in terms of interest rates and the uncertainty of employment are now being lent enormous amounts of money. And it sets the stage for the crisis of 2007.

Bringing us to the 21st century: America is mired in debt. How did that happen and where do we go from here?

You don’t have an economy that’s based on wages anymore. You have an economy that’s based on lending and asset appreciations, so that people earn much more from their houses over the next 30 years then they do from wage increases.

The median wage is stagnant between 1969 and today. It’s more money going to the very top. It’s this inequality that makes it so profitable for companies like General Electric to move away from making things to lending money.

In postwar America, we have a rising economy based on a rising wage. After 1970, we have a rising economy based on rising debts, which I think is a much less stable kind of economy.

Read more about it so that you don’t personally allow history to repeat itself. Buy Debtor Nation here.