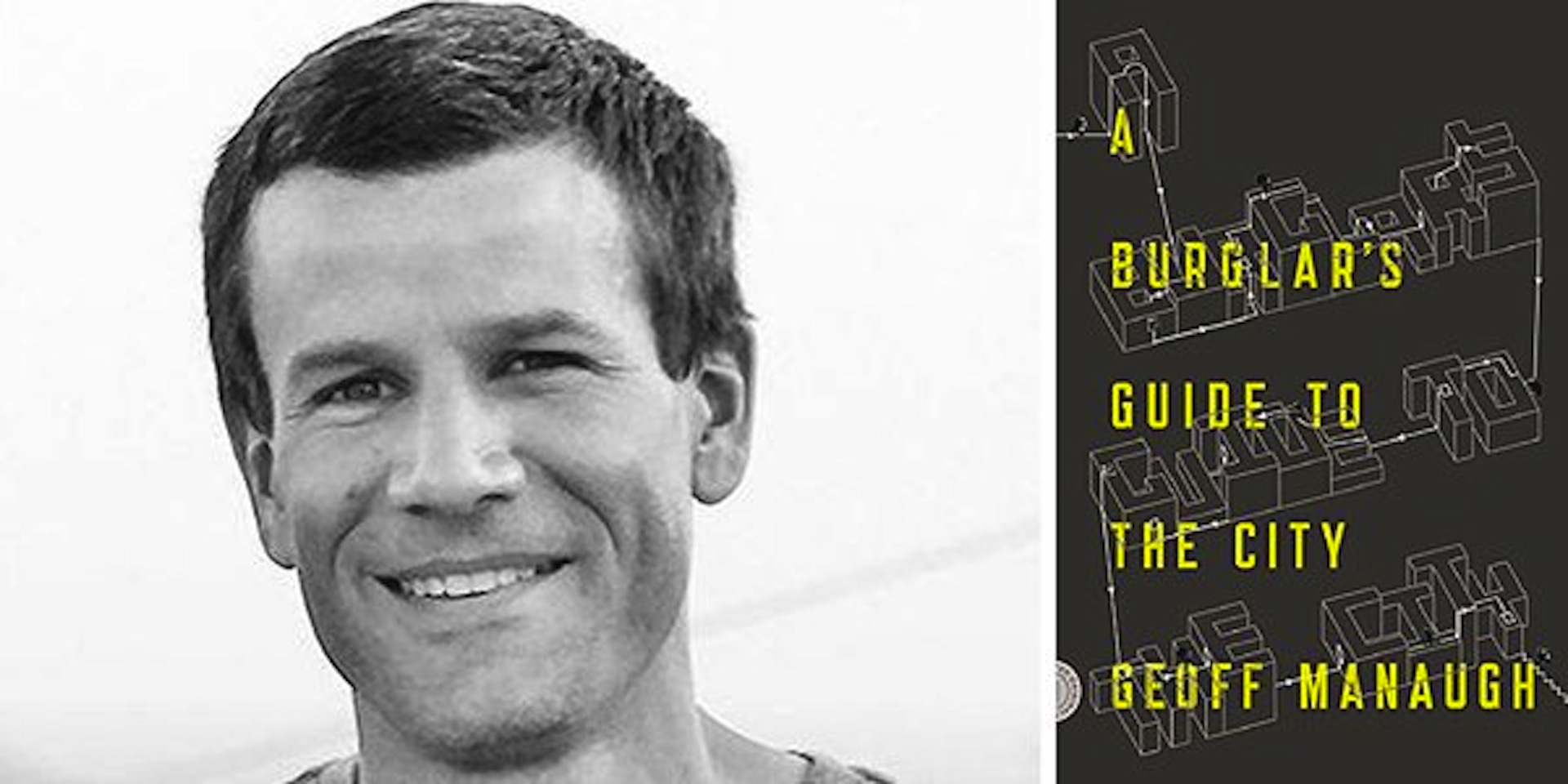

There has always been a strange connection between architecture and burglary; Geoff Manaugh makes that connection and more in his book, A Burglar’s Guide To The City. Although the “art” of burglary is actually dying, due to a world of surveillance cameras and advanced electronic security, Geoff suggests that the perfect heist may actually be waiting in the wings despite advanced technology and Big Brother watching us. It’s all in the planning, the psychology, and the way tech can be manipulated to dishonest ends. As well, he writes about how old-school burglars are lending their expertise to security companies, how government agencies like the FBI sanction break-ins, and how movies and TV romanticize a crime that continues to fascinate in its evil attention to detail.

Geoff is a freelance journalist who, although not trained as an architect, has a large following on his BLDGBLOG. The book is a result of three years of hands-on research, examining historic heists, researching burglary as far back as ancient Rome, and taking a closer look at some of the architecture we take for granted, including doors, floors, air ducts and crawl spaces.

Here, we ask Geoff to help us case the joint.

Great idea for a book! You’ve been covering architecture for a long time; has there been some kind of evil spark in the back of your mind leading you to the dark side?

There is a really vibrant architectural conversation happening out there, but it’s not in the realm of people designing buildings. It’s in the realm of people abusing or misusing buildings. That seemed pretty compelling to me. Every time I would read a police report or see on the news a jewelry store owner explaining how the burglars came in through the wall and broke into the safe without ever entering the room, there was a very, very clear foregrounding of architecture — but it was in the service of using architecture in totally unexpected and fairly aggressive ways. It seemed that there was no book that connected the dots. After all, planning a heist is really a design operation, and if you can put that into the context of what architects do, you realize that burglars are really just counter-architects. They look at a building and they find new ways to get from one room to the next, or even to get from one building to the next. There is just something so spatially fascinating about that.

What kind of reactions do people have to burglary as a crime? I assume it doesn’t receive the same horrified reaction of some more violent crimes that cause physical or bodily harm.

There are two equal but opposite responses to burglary. Burglary lends itself so well to a kind of romanticization. It has that feeling of an ingenious act of connection, where someone finds a way to get from a sewer system into a bank vault, or they find a way to get from the attic into a money room of a hotel. There is something ingenious and strange about that, as if they solved a puzzle.

On the flip side, burglary really does have an emotional impact. You realize that someone has been in your home and has been rifling through your things, or they have made you mistrust your own neighbors or even your own family members. There is a real sense of emotional violation.

Burglary does not necessarily have to involve theft. It’s the intent to commit any criminal act while in a building that you don’t have permission to be in. It’s a very peculiar crime, and it’s really intimately tied to architecture. If you don’t have buildings, you can’t have burglars. Their very existence is dependent upon architecture. There is something just existentially strange about that.

Burglary is, above all, a psychological and cerebral crime, right? It involves a lot of thought and planning.

In the book, one guy in Toronto figured out a way to use the city’s fire code to help choose what buildings to break into. There was another example in Los Angeles where [burglars] used the storm sewer beneath the city as their way in and out of bank robberies; so they not only broke in by tunneling through the storm sewer network, but their getaway was actually a seven-mile underground route from the bank to a stream. We tend not to think that knowing a lot about buildings would be a risk; if you understand the door plans or you know where the doors are, somehow that constitutes a threat. We think about that when it comes to questions of terrorism. It’s fascinating to think that architectural knowledge is also risky.

In the beginning of the book, you describe an architect-turned-burglar who designed and then robbed his own building!

It’s a fundamental betrayal at the heart of the city: someone who is a creator figure, an architect. Then they come back to break into and violate the thing that was created. Someone comes back to betray the thing that they made.

In the world of burglary, I would imagine that cops and detectives are constantly outwitted by burglars, and vice versa. Is there a lot of one-upmanship and plot twists?

You have ingenuity and innovation happening on both sides. You have examples where criminals are the ones being outwitted by cops who have set up something like the Capture House program, fake apartments run by the police. You’re not even breaking into a real apartment. It’s a surrogate apartment that the cops set up.

Usually, the burglars outwit the cops though low-fi means. A building could have a multimillion-dollar surveillance system with thermal cameras and detectors, and all it takes is somebody with electrical tape and hairspray and they can make the entire system go down. It’s a constant back-and-forth battle between different types of innovation, and between super-high-tech and really low-fi.

You also write about reform burglars who help the police and security companies. How can we be sure that they are reformed?

There, you just get into a sociological question about trust. Do you believe in redemption? Do you believe that people can change? In that case, you just have to take someone at their word that they are no longer engaging in this activity.

The guy in the book, who is a reform burglar, ironically, works in the security industry now. He has a hands-on, granular knowledge of what it takes to break into certain kinds of buildings. On the other hand, there is something alarming and “double-agent”-like about that. By working in the security industry, this guy is just gaining more knowledge for his illicit pursuits. It’s really a question about whether you believe that humans can change, and whether or not trust is the currency that holds society together, or if you need something more vigorous. That’s when we get into whether we need security.

Has the digital age changed the game?

The minute you start adding these high-tech approaches, you get into a totally different and really exciting field. Burglary thefts are way down while identity thefts are way up. So if your goal is to get as much money as possible in as short a time as possible, burglary is not the way to go. As you scale up, you get into some incredible scenarios: traffic management systems, street light patterns, mobile sensors for traffic. It gets into a whole new scale for the possibilities of burglary.

Burglary on a large enough scale is almost identical to terrorism. Managing traffic, for instance, becomes an integral part of the plot. I definitely think we are going to see a real-life example of that kind of thing in the years to come, because it seems so easy to rearrange a vulnerable city. The wrong people are going to figure out how to do this.

Does burglary differ from city to city? Is burglary different in New York than, say, Los Angeles?

There are definitely continuities that go back literally thousands of years to ancient Rome and the kind of places a burglar might hit. There is almost like a “speciation” amongst burglars, so you do see different approaches in different cities. Some of it literally just boils down to “what’s there.”

If you are in a small town that doesn’t have a lot of jewelry stores, but does have a bank in the middle of town, that bank is going to be more of a target. Some cities are more prone to tunneling jobs, for example, than others. You’ll see tunneling jobs in London and Berlin and South America, because they have more clay, mud and sandy soils, which are easier to dig through. In New York City, you are dealing with billion-year-old bedrock. It’s pretty unlikely that you are going to tunnel into a bank vault.

When you go above ground, you get the infrastructure of the city itself, so you start getting into things like where the freeways are, what routes of escape might there be, public transit. We are making decisions right now, as a society, in terms of the infrastructure that we fund. [These decisions] will have criminal side effects, and some of them are impossible to imagine. We’re setting the stage for some future event, and we don’t even know what that event might be.

Is burglary a dying art?

It’s a funny phrase. You can call it a dying art. You can call it a dormant science. You can call it a lot of things. The numbers have really plummeted. In New York, it’s astonishing that from 1990 to the present moment, burglary has gone down 87%, which is really incredible. So it is certainly on the list of endangered crimes. On the other hand, considering Zillow and all the real estate access plans and internal information we have about houses, and on social media with people posting when they are not home, we are entering an era when unexpected new vulnerabilities are emerging. I would be very interested to see if burglary has an uptick in statistics in the years to come.